Today, the name “Disney” is synonymous with debate

Every release, every announcement, and every live-action remake seems to divide audiences.

Conversations center on corporate decisions, political agendas, modifications to classic characters, and a perceived decline in quality within its flagship franchises. From Marvel to animated classics like “The Little Mermaid” or “Snow White,” the company Walt Disney founded finds itself at the center of a cultural storm.

But this conversation, so anchored in the present, often forgets or confuses the man who started it all.

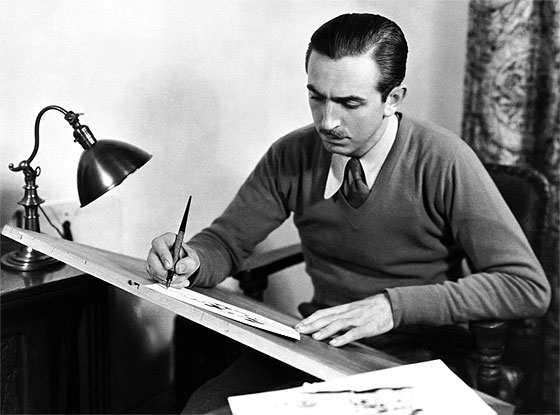

This article does not seek to defend the corporation’s 2025 decisions. Instead, it seeks to press “pause” on the current noise and rewind to the beginning, to rediscover why the name “Disney” became synonymous with magic in the first place. This is a reminder about Walt Disney: the artist, the innovator, and the tenacious entrepreneur whose impact on the 20th century is, quite simply, undeniable.

The Rejected Artist

Walt Disney’s path to success was not a smooth one. He didn’t leave school to be hired by a major studio; in fact, his first attempts were resounding failures.

His first animation company, Laugh-O-Gram Studio, founded in Kansas City, went bankrupt. With little more than his drawing tools and an idea, he moved to Hollywood. There, just as he was beginning to find success with a character named Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, he was betrayed by his distributor, who seized the rights to the character and poached nearly his entire animation team.

It was a devastating blow that would have ended many careers. But it was on that train ride back, defeated and without his creation, that legend says Mickey Mouse was born. Walt wasn’t just a dreamer; he was a fighter who turned bankruptcy and betrayal into the starting point of an empire.

Innovation as DNA

Walt’s love for drawing and animation was the foundation of everything, but his true genius lay in his refusal to accept the technical limitations of his time.

When sound came to cinema, other studios treated cartoons as a secondary product. Walt saw a revolution. “Steamboat Willie” (1928) was not the first animation with sound, but it was the first to perfectly synchronize music, effects, and action with obsessive precision. It transformed animation from a silent visual spectacle into a complete audiovisual experience.

Shortly after, he bet everything on the expensive Technicolor process for his short “Flowers and Trees” (1932), winning the first Oscar for an animated short and establishing color as the new industry standard.

The “Disney Folly” That Changed Cinema

Walt’s greatest innovation, and his biggest risk, was his conviction that animation could tell deep stories. In 1934, he announced his plan to produce a feature-length animated film: “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

The industry mocked him. The project was dubbed “Disney’s Folly.” Everyone, including his brother and partner Roy Disney, warned him that no one—absolutely no one—would pay to watch an 80-minute cartoon. It was believed audiences would get bored, the bright colors would tire their eyes, and the studio would go straight to bankruptcy.

Walt didn’t listen. He mortgaged his house and risked his entire studio to finance the project. When “Snow White” premiered in 1937, it wasn’t just a success; it was a cultural and commercial phenomenon that redefined entertainment. It not only saved the company but created the animated feature film industry as we know it. It proved that drawings could evoke tears, laughter, and suspense with the same power as a live-action film.

The Visionary Who Built the Dream

Walt’s empire was not limited to the screen. His vision expanded into the physical world. In an era when amusement parks were often seen as dirty, chaotic, and un-family-friendly places, Walt imagined something different.

He created Disneyland (1955), the first “theme park.” It wasn’t a collection of rides; it was an immersive, clean, and meticulously designed environment where families could step inside and walk through the worlds they had only seen in his films. It was an extension of his love for storytelling, applied to physical space.

Conclusion: Separating the Creator from the Corporation

Today, it is easy, and perhaps justified, to criticize the direction of The Walt Disney Company. The decisions of a global, multi-billion dollar conglomerate, decades after its founder’s death, respond to market logic, shareholder pressures, and cultural climates that Walt Disney never knew.

But it is a mistake to project the controversies of 2025 onto the historical figure of the founder. One can, and should, separate the man from the modern brand.

Walt Disney’s legacy is not the latest Marvel movie or the script of a politically correct remake. His legacy is the invention of the animated feature film, the revolution of sound and color, the creation of the theme park, and the proof that a stubborn love for drawing and creativity can, quite literally, change the world. The brand may be up for debate; the innovator’s legacy is history.